Week-to-Week: The Golden Globes are the best argument against the Golden Globes

They should have died, but their life isn't all bad (okay, it's mostly bad)

Week-to-Week is the weekly-ish newsletter of Episodic Medium, home to weekly television reviews and media industry analysis, written by its editor-in-chief, Myles McNutt. To receive future newsletters and updates on the shows we cover for paid subscribers, join for free.

“I don’t know about award shows, but when they get it right it makes sense.”

We were right to want to kill the Golden Globes. Long a corrupt institution, it was almost frustrating that it took a post-2020 racial reckoning to bring it down, and I still wonder if it would have persevered in its existing form if not for the pandemic keeping award season from operating in full flight. But with Hollywood reflecting on its complicity in white supremacy, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association was undone, and with it an award show where a couple hundred shadowy people took bribes, wielded influence, and deserved every bit of criticism it was ever given.

And yet somehow, the Golden Globes returned. And while I’d still probably feel better if they ceased to exist entirely, I have come to terms with the fact that I am glad the Golden Globes are still a thing. While once a distinctly corrupt institution, the version that has settled into place in the three years since its 2023 return is representative of everything wrong about award season. Owned and operated since the 2024 ceremony by the Penske Media conglomerate that runs nearly every trade publication, they are a stimulus project, not an award show. They exist to prop up the industrial system that allowed the Golden Globes to matter for so many years, and having a shoddily-produced, three-hour reminder of that reality is doing more work to undermine the awards ecosystem than their absence.

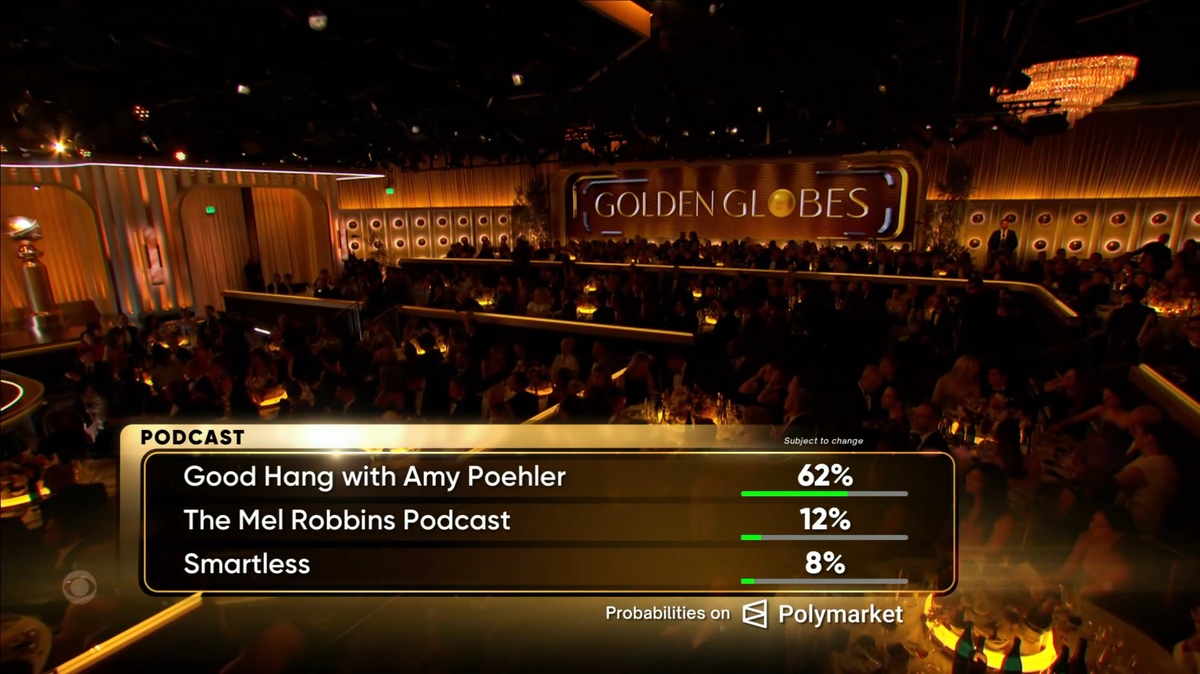

The 2026 Golden Globes were a profound embarrassment of a broadcast. The facts of this year’s new podcast category were bad enough in the buildup to the awards, whether it was the pay-for-play promotional packages being sold to extremist eligible podcasts (as determined by Penske-owned Luminate) or the fact they pushed the Original Score award from the broadcast to make way for it (congrats, Ludwig). But it managed to get worse when, ahead of the award’s presentation, Variety’s Marc Malkin informed us what the Globes’ “probability partner” Polymarket was telling us about the odds for the "pozcast" category, and then the piece d’resistance: after foregoing clips from nominated performances in favor of bizarre Google Maps geolocation in the Beverly Hilton ballroom, they showed video clips from the podcasts before ultimately bestowing the inaugural award to Good Hang with Amy Poehler.

It embodies so much of what was wrong with these three hours of television. The color commentary from Entertainment Tonight host Kevin Frazier and Malkin was garish, injecting celebrity journalism patter into the broadcast with zero upside. It was also occasionally inaccurate: they prattled on about Adolescence season two when no such thing exists, for example. No one who was producing this show seemed to have any modicum of respect for the idea of awards as anything other than the reason Penske bought them: a vessel by which money can be made, whether in FYC ads for the films that gain Oscars momentum, SEO hits on their article about whether Chalamet mentioned Jenner, hideous cross-promotion of Paramount’s UFC rights deal, or whatever Polymarket paid for their partnership.

In other words, the Golden Globes broadcast is the best possible argument for the illegitimacy of the Golden Globes, but it raises the question: do we give it legitimacy by watching, or reporting, or being happy with someone winning? When news stories boil the night down to winners and losers, they don’t open with the disclaimer that the broadcast regularly revealed the emptiness of the ritual. When Wanda Sykes goes viral for her “give no fucks” critique of Ricky Gervais’ transphobia, or when Nikki Glaser gets credit for an opening monologue that called out CBS News on CBS, are we accepting the rest of the bullshit? And if we celebrate the Globes validating a performer like Rhea Seehorn in a way that creates the momentum they need to win legitimate awards, are we the problem?

My answer is no, because the last five years have proven that there is nothing that will stop Hollywood from treating the Golden Globes like they matter, and so whether out of professional obligation or not, it only makes sense to try to leverage them for something meaningful. If people watching at home seek out The Secret Agent after its wins for Non-English Language film and Best Actor - Drama, that’s a win for people hoping to see a film that’s yet to reach more than 136 screens in the United States. And when you see how much this recognition matters to a performer like Teyena Taylor, doesn’t it feel like we can accept the positive outcomes this has on the art of film and television. Was CBS’ broadcast supporting any of that? No, of course not. Does Penske actually care about that? Not even a little bit. But we care, and many of the people on that stage cared, and to erase all of that based on the fact that this shouldn’t matter strikes me as short-sighted.

And I can’t pretend that Penske is entirely wrong about the cultural function of the award show, loathsome as the production might have been. Heated Rivalry isn’t even eligible for the Golden Globes (because Canada), but there was Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie extending their takeover of the internet into the “real world.” Whether on the red carpet or in presenting Supporting TV Actress, it felt like a meaningful evolution of their internet takeover for them to be in that room with those people, with higher stakes than when megastars like George Clooney or Julia Roberts presented awards later in the broadcast. And based on how much coverage they received—Williams was literally the first person who appeared in the red carpet montage at the beginning of the show, director Glenn Weiss cut to them during Glaser’s monologue, and Glaser did a full joke for them later on—Penske and CBS knew people were clamoring to see more from their new obsession. It’s a throwback to an earlier age where the award show was the only place to see celebrities outside of their films; now, we have constant access to most celebrities on social media (or, clearly, podcasts), but the way they treated these young stars reinforces that presence in this space still matters.

Penske’s version of that space is odious and toxic, a self-serving paean to the industrial hierarchies we were reminded of every time the camera conspicuously landed on the executives who are so confident in their place in this ritual one of them (Sarandos) agreed to lampoon it on The Studio. But as much as I will tell anyone and everyone of the Globes’ current corruptions, as well as its long history of illegitimacy, I’m not going to deny the catharsis of Seehorn getting her due after being overlooked so long for Better Call Saul. If we’re never going to break free of the co-dependence between awards and the industry they serve, all we can do is claim victories where they are, and keep doing what we can to make the truths of award season visible in whatever ways we can.

It won’t kill the Golden Globes, but that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to gain.

Episodic Observations

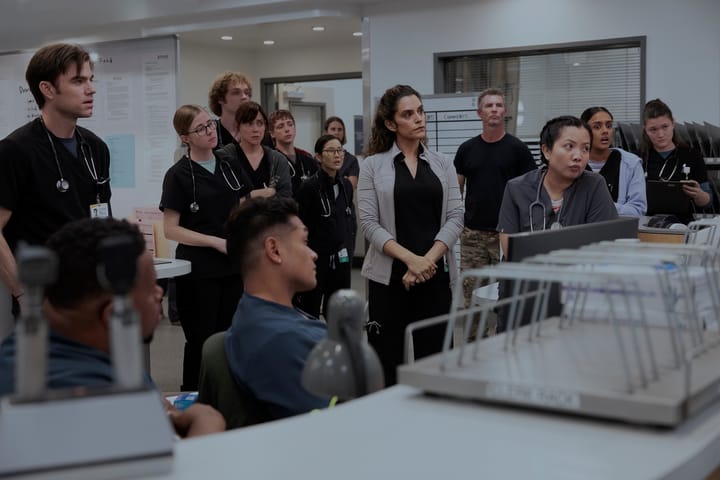

- Extreme overlap between Emmys and Globes eligibility meant that outside of Seehorn, there were no real changes on the TV side: The Pitt, The Studio, and Adolescence won everything they won at the Emmys except in cases of overlap (the shared supporting category).

- No, I do not know how the official Golden Globes account managed to use two almost identical images of Kumail Nanjiani and Emily Gordon for their clips. (We put on Eternals while I was editing this, though, so maybe they knew.)

- Judd Apatow got too much time for his presentation of Best Director, but I really appreciated how my first thought was “Is he a good enough director to be presenting this?” and then it became the thesis of his presentation. That plus the ongoing dragging of The Martian competing as a comedy? Written for me. (I would clock, though, that his joke about not being able to pronounce the winner felt like a weird attack on Jafar Panahi).

- It was clear the writers of the broadcast are online enough to feel like Heated Rivalry is everywhere and that every famous person has seen it, but they wrote that bit to account for a relatively lukewarm response, hence the “that’s a maybe.” (Also, the less said about that cringeworthy UFC preamble, the better)

- A striking absence of outright politics in speeches, which is one of the true fundamental goods of award shows. Not sure if they were given explicit warnings about this, but we were missing more than vague references to our present moment.

- Based on how many people conspicuously thanked the somewhat awkward “Golden Globes voters,” I am presuming they were all warned not to thank the Hollywood Foreign Press Association out of habit?

- Ayo Edeberi and Hailee Steinfeld sold the hell out of their presenting patter, short as it was. I want to see them in a comedy.

- I know that he’s a realist, who has spent years serving large corporate masters in the interest of creating the freedom to make the movies he wants otherwise, but Ryan Coogler just accepting the way the Globes are using the Box Office and Cinematic Achievement Award to honor films like Sinners and Barbie while ignoring them for more traditional Oscar fare in bigger categories still bums me out, y’know? And although I have lots of feelings about the way people reacted to the reporting around its box office results, to miss an opportunity to call out the trade press and its systems for their failure to see the film’s box office success coming kind of whomps.

Comments ()