Week-to-Week: The Conspicuous Contempt of the 2025 Emmy Broadcast

Voters chose rewarding winners; the broadcast insulted them

Week-to-Week is the weekly-ish newsletter of Episodic Medium, where I respond to ongoing developments within television and the media industries at large. A reminder we are halfway through our yearly subscription drive, with our last 20% off sale on yearly subscriptions on through 9/30. To learn more on what we're covering for paid subscribers, see our Fall Schedule.

The pretense of the Emmy Awards is that the people voting on them watch everything that’s been nominated and reward the best performance.

This is the case for all media award shows, of course, but there’s a big difference between watching 10 movies to vote for Best Picture and watching an entire year of television. It means that compared to other award shows, there is a conception that the people voting on the Emmys are far less likely to have actually seen the shows in question. They maybe attended some FYC events, and probably sampled some of the screeners sent to them, but the chances of any Emmy voter watching every single episode submitted for Drama, Comedy, and Limited Series in all categories is extremely low.

Awards are of course subjective, and I don’t always go into a category with a definitive opinion on who “should” win. One constant, though, is my appreciation for any win that clearly suggests the voters watched the shows in question. When Jeff Hiller was a surprise nominee—some social media posts didn’t even have his headshot—for Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series in HBO’s Somebody, Somewhere, it meant that he couldn’t be ignored: at least some voters would sample a small show they may have missed as it finishes out its three season run. And so when Hiller won an admittedly fairly open category, it felt distinctly like a form of justice: an amazing performance was seen, admired, and rewarded.

And while we can talk about the broadcast itself in a second, the early section of this year’s ceremony was defined by categories where it felt like voters were paying attention. Kathy Bates would have been a deserving winner for Matlock, but Britt Lower’s win for Severance reflects a turn that expanded on a breakout performance in the show’s first season (where she wasn’t even nominated). Carrie Coon would have earned an Emmy as one of the myriad White Lotus nominees, but voters clearly watched The Pitt if they were willing to see Katherine LaNasa give a truly supporting performance. The same would have been true for White Lotus' Walton Goggins, but it’s comforting that voters who watched Severance understood how undeniable Tramell Tillman—the first Black man to win Supporting Actor in a drama series—was as Milchick’s role expanded in the second season.

For the readers of this newsletter, this framework for the Emmy Awards makes sense. We’ve been watching Hannah Einbinder lose despite giving a co-lead performance on Hacks for three years, and so her win resonates as a response to years of discourse. We’ve watched all of this television, and so who wins matters. But this is in direct opposition to the reality that a majority of people who watched the Emmys may have never seen a single show that won an award. If a viewer watching at home doesn’t have subscriptions to HBO Max and Apple TV+, they missed out on nearly every winner across the Comedy and Drama categories, and the chances that viewer also has normal HBO and watched Somebody, Somewhere are…low. The one exception to this is Netflix’s Adolescence, which is the service’s second-highest viewed show ever, but would any of those viewers also be watching CBS on a Sunday night?

I raise this point because it helps explain the conflict generated by the production’s one big bit for host Nate Bargatze. After an SNL-style Cold Open offering an honestly useful retelling of the past twenty years of television history in the vein of his viral “Washington’s Dream” sketch (I could see using it in class), Bargatze skipped the traditional opening monologue slot, returning to the stage following Seth Rogen’s win for Comedy Actor for The Studio to explain the night’s premise: he will donate $100,000 to the Boys and Girls Club of America, but that number will go up and down based on how winners deal with their 45-second time limit for their speeches. Short speeches add money to the pot; long speeches pull it from the hands of kids in need.

This is obviously not the first time where concerns over a show running long have become part of the narrative of an award show. Back in 2006, nearly 20 years ago, Conan O’Brien infamously ran a similar bit trying to add “stakes” to the length of the Emmys broadcast, purporting to lock Bob Newhart in a box with only three hours of air. At regular intervals, the show cuts from elements of the broadcast that you could arguably cut for time (like the accountants) to Newhart and a countdown clock, in many ways an active critique of the networks’ concern over the show running long. We know he’s not going to kill Bob Newhart, but the bit gives Conan space to argue that making good television should come before affiliates’ concern over the delay of the local news.

Bargatze’s bit is theoretically framed the same way, but runs into several problems of both conception and execution. Right after Jennifer Coolidge presented the award for Comedy Actress to Jean Smart, Bargatze appeared backstage to answer a frequently asked question: would they also be penalizing presenters for going over, given that—for example—Coolidge had improvised well beyond her scripted bit? No, he explained: “We’re only going to penalize the people who worked the hardest to be here.” It’s a funny joke until you realize that this is literally what Bargatze and the producers would do throughout the evening, in an unavoidably intrusive way with none of this self-awareness.

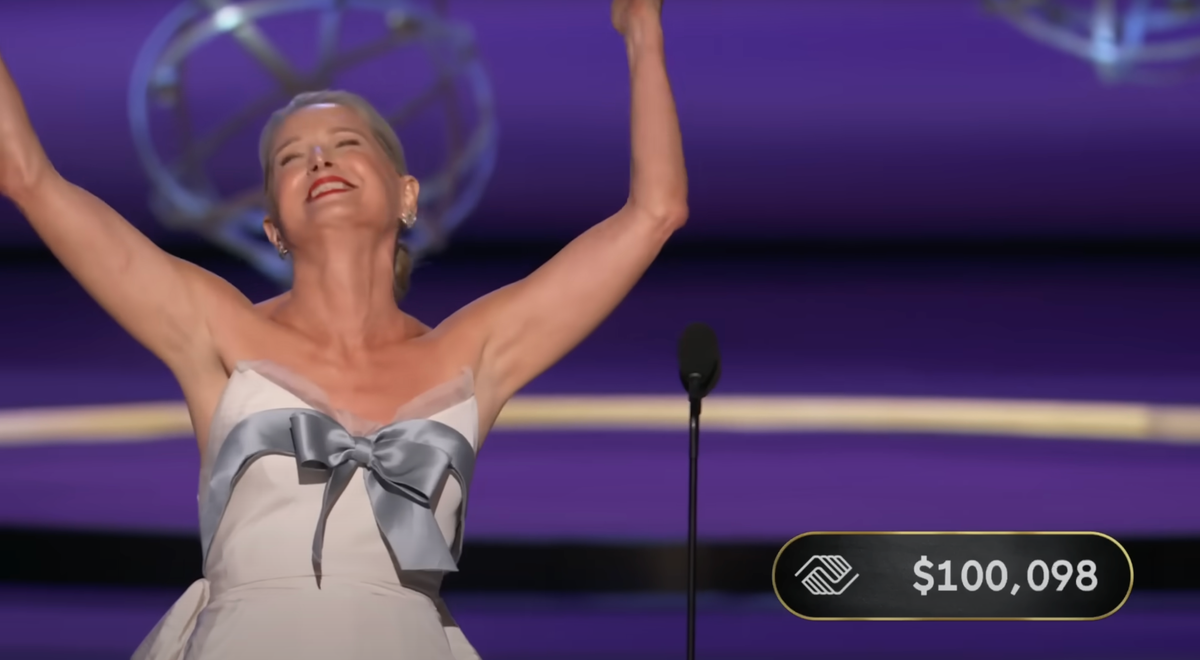

The intrusion is distinctly felt by those of us who had watched all the shows that won awards throughout the broadcast. Any literate viewer knows going into the broadcast that there is no universe where this would end with anything other than a sizable donation to the Boys and Girls Club. However, we still have to watch the show actively punish and shame people we admire for daring to take their moment to celebrate an incredible achievement. Katherine LaNasa was “fined” for an extended “Whooo” at the end of her speech, while Adolescence’s Owen Cooper went over time telling an inspiring story of how drama classes brought him to the Emmys stage so unexpectedly (Bargatze did offer to cover his costs, for the record). The idea that Jeff Hiller would win an Emmy but then have to worry that a giant number would pop up on screen behind him and start going down is an insult to his accomplishment, and the fact that the show would have a chyron pop up onscreen when the money started going down is an insult to our investment in these honors (pictured: Adolescence director Philip Barantini).

So why was it there? Because the producers of this broadcast don’t believe that the audience at home is invested in who wins and loses. They believe that viewers at home wouldn’t even know who Katherine LaNasa and Jeff Hiller were, and that the donation bit would keep them engaged in an award show they were watching because they don’t like sports and live events are the one other thing that moves the needle as linear broadcast television fades into cultural irrelevancy. They believed this so much that they gave Bargatze absolutely nothing else to do: given that he nervously bungled half his introductions of presenters, his primary role in this broadcast was to reinforce its contempt for the night’s winners.

Based on my social feeds, and the conversation among subscribers in our Loyal Viewer Discord, this was a miscalculation. But although obsessive TV fans and television journalists are arguably the primary audience for the Emmy Awards, they’re probably not the majority of the audience for the Emmy Awards broadcast, and so it’s entirely possible that this created a point of interest for viewers at home who don’t know Hacks from Hacksaw Jim Duggan. If we were to leave our “echo chambers”—my TV-centric Bluesky feed, this newsletter—and seek out the viewers who have never seen The Pitt and didn’t even know The Studio existed, it seems possible this running gag was actually what they connected with most in the entire broadcast.

But here’s the thing: the Emmys should be an echo chamber for people who love TV. It should take the Academy President’s words about the power of television to heart, and create a broadcast that invites people into the culture of television as opposed to operating outside of it. It was clear from the response to Stephen Colbert and the boos for Congress’ cuts to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting that this is a room invested in TV’s power in this particular moment. Let that be the goal of the broadcast, and let the people who voters chose to represent that power have their moments, and if that means people tune out over a speech that runs over, so be it. While nobody wants to have a show full of Adrien Brodys, we also want for a moment like Dan Gilroy’s most-deserved writing win for Andor to have the time to reflect that show’s importance to our current circumstances.

And if people haven’t seen Andor and don’t have the context they need to respect that, the Emmys should exist to give it to them.

Stray observations

- The choice to send Elizabeth Banks up with a whole spiel about the five women nominated for Directing a Limited Series when Adolescence was basically guaranteed to win, and was the single man nominated? Impossibly dumb.

- I’m furious that Seth Rogen was onstage four times and never once thanked Sarah Polley, even when winning for directing the episode she appeared in.

- Hiller and Cristin Milioti’s (deserved) win for The Penguin kept the acting races from being a complete sweep for streaming services, although the latter is on a technicality, since The Penguin was originally going to be a Max-exclusive.

- The Gilmore Girls reunion and the Everybody Loves Raymond teamup with Romano and Garrett represented the best presentations of the evening, which was a real victory for 2000s television. It was also deeply bankrupt, given how the Emmys so ignored Lauren Graham and Gilmore Girls that they completely overhauled their nomination process to try to correct it, and ended up nominating Kevin James instead.

- As for what these wins say for the future of television, it’s clear those who work in television see The Pitt as a ray of hope for a return to longer episode orders and viable careers. I’m not surprised that won out over Severance’s art television approach when push came to shove, although it feels better when you consider the wins for Lower and Tillman ensured Severance was well-regarded (even if both shows ended up losing directing to Slow Horses, much as Shogun lost writing to Slow Horses last year).

- A reminder that if you were inspired to catch up on any of this year's big winners, we covered nearly all of them episodically here at Episodic Medium, and you'll find them hyperlinked throughout. We'll address the absence of Slow Horses with season five in a few weeks.

Comments ()