Review: A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms, "The Hedge Knight" | Season 1, Episode 1

HBO launches its latest quest for more of the same (but different)

Welcome to our coverage of HBO's A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms. As with all our coverage, the first review is free, but subsequent reviews will be exclusively for paid subscribers. To join the conversation and support the work we're doing, consider upgrading today.

It’s easy to be cynical about the franchising of media broadly, and it’s perhaps even easier with Game of Thrones. What was once a successful but niche set of fantasy novels became a global sensation when the HBO series debuted fifteen years ago this April, and it spawned everything you’d expect: the merch, the books (I wrote one of them!), and of course the spinoffs.

It’s that plural that becomes the problem. We remember the “bake-off” as the show wound down, with five competing projects angling for attention. We remember the busted pilot featuring Naomi Watts, suggesting that HBO wasn’t just going to shove out the first project they invested in. However, we have also seen two seasons of House of the Dragon, a show engineered to deliver the hallmarks of the franchise within the recognizable package of the Targaryen dynasty. While not without its strengths, it’s a show so anxious about moving beyond Game of Thrones that it literally reuses the theme song, in case we failed to otherwise spot the resemblance.

Spinoffs and other forms of derivative programming are driven by that core logic: more of what people already like and have invested in. There’s no avoiding the cynicism of relying on the familiar over the new, but there’s also always the possibility of finding a new perspective within the cover of success. More people will tune into a show set in Westeros than set in another context, so how could that be used to the advantage of a story worth telling?

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms has become the second spin-off of Game of Thrones because HBO and Warner Bros. Discovery have decided the best approach to navigating this cynicism is to rely on the credibility of George R.R. Martin, only creating spinoffs that he himself brought to life. House of the Dragon is loosely adapting his own diegetic history Fire & Blood, albeit apparently in ways increasingly divergent from his intent based on his now deleted blog posts, and A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms adapts his Tales of Dunk and Egg novellas. The difference, though, is that whereas the former is based on source material Martin specifically wrote in the aftermath of the show becoming a phenomenon, the three novellas that make up the source material for A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms were all published well before those babies were being named Daenerys. These stories don’t exist because HBO wanted a TV show—they exist because George R.R. Martin wanted to explore the contours of the world he created.

I’m writing this in a vacuum, before the embargo breaks, but I know many reviews are going to talk about the way “The Hedge Knight”—which shares its name with the first novella—positions itself relative to its television forebears. As Dunk finishes burying Ser Arlan of Pennytree, he’s envisioning what his life looks like. He could sell the horses, but it would mean selling the only meaning his life has. He was just an orphan boy when Arlan took him in, and he knows nothing other than traveling Westeros offering services from lord to lord. All he can do is take what Arlan left him—the horses, his armor, his sword—and journey into the world to stake his claim to the heroism and chivalry the title of knight represents, a notion briefly set to the opening chords of Ramin Djawadi’s theme song so good they used it twice.

And then we hard cut to Dunk violently shitting behind a tree.

It’s a moment without a clear analogue within Martin’s novella, which I’m listening to in audiobook form (read by Viserys himself, Harry Lloyd) in tandem with the series. Yes, the early section of Martin’s novella carries a lighter tone overall compared to the epic scale of A Song of Ice and Fire, but it never seems to be sending a clear message that “this isn’t like those.” It’s still about detailed descriptions of heraldry, and the emphasis on the food being consumed, and everything you might ascribe to Martin’s writing. It just is those things without being bogged down in mythology, and in the epic scale that would eventually swallow the entire series so much so that Martin will never finish it (no matter his intentions).

But for television, it is clear that creator Ira Parker was given the specific task of making clear this is a show driven by a sensibility Game of Thrones struggled to find as it grew in scale. There was certainly comedy in Game of Thrones, but its world became too weary for much of it in later seasons. It’s telling, I would argue, that this show came to take its name from the one episode in the final season that felt like it had the narrative space to find those different shades of the show. Written by Bryan Cogman, “A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms” was a calm before the storm of the Battle of Winterfell, when all the characters could do was contemplate their lives and their humanity in the face of a supernatural threat. It was the highlight of that season from a character perspective, anchored by the emotion of Jaime knighting Brienne ahead of the battle.

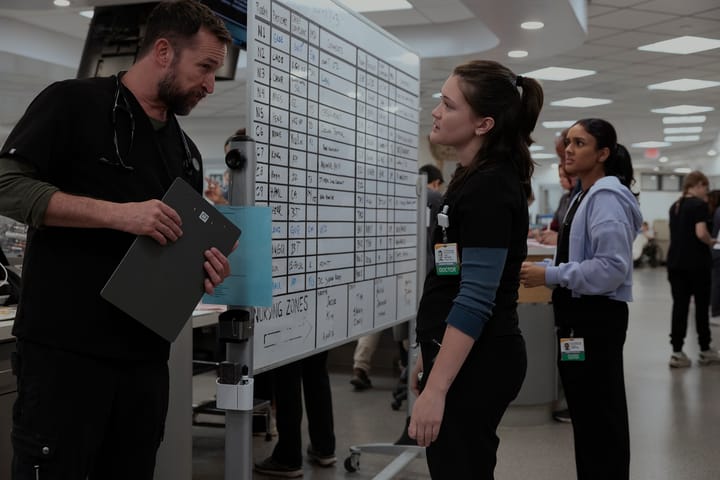

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms is similarly interested in the idea of what it means to be a knight, but Ser Duncan the Tall’s challenges are distinct from Brienne’s. If gender was what held Brienne back from claiming her place within Westeros, it’s class that stands in Dunk’s way. He was an orphan squiring for a Hedge Knight, a term the show kind of glosses over a bit but emerges clear enough: a knight who has no castle, forced to travel from place to place in search of meals and lodging and a reason to keep existing. They’re not sellswords, exactly, although the distinction isn’t all that clear. My best understanding without reading the entire set of stories is that Hedge Knights are still loyal to the idea of knighthood, and the way Dunk presents himself here is evidence of that. He is effectively cosplaying as a knight, cobbling together an idea of himself that everyone around him receives as aspirational.

Something I thought was interesting in comparing the two was how I interpreted the question of Dunk’s knighthood. Listening to the audiobook, it’s implied that Ser Arlan’s swift death would have left little time to knight his squire, but there’s nothing that would necessarily call it into question. However, in the show the way the narrative articulates his impostor syndrome made me question if it even happened. He’s defensive when he first encounters Egg at the inn, and it’s especially true when he speaks to the Master of Games who reads him immediately. It’s true that this could just come from his lowly standing as a Hedge Knight, but when he goes back into his memory we only see Ser Arlan spitting in response to the question of whether Dunk is meant to follow in his footsteps. Even the existence of those flashbacks—used as comic cutaways—calls the event into question, given that we could be seeing the moment he knighted him but aren’t.

Regardless of how that’s supposed to land, I don’t mean to suggest we interpret Dunk as a fraud. It’s more a part of the aforementioned comedy, like bumping his head on the door going in and out of that meeting. He only knows the life he has, and that means being loyal to the idea of being a knight, regardless of whether a formal knighting ever took place. He still feels like an impostor either way, and the episode becomes about how his performance is judged by everyone around him, whether it’s the oddly perceptive Egg or the women surrounding Manfred Dondarion, the man whose patronage is necessary to let him continue on with the charade.

This setup is pulled largely from the novella, but there’s some shifts in timeline. Here, Egg doesn’t show up until the episode’s end, after Dunk has spent an entire day in Ashford exploring the new life he’s trying to build for himself. By comparison, Egg’s arrival comes before everything Dunk does in Ashford in the novella, meaning that their partnership becomes part of the story earlier. The result is a much closer focus on Dunk as a solo traveler, acting the knight while his inner thoughts—or the thoughts of his horse companions—betray him. It creates more space for moments like his conversation with the women in Manfred’s retinue whose mockery triggers his anxiety: they’re teasing him more than they’re mocking him, but they’re tapping into the uncertainty that drives him, and he responds with a practiced confidence that needs more practice. Peter Claffey carries himself well throughout, but watching him wander through that first night at Ashford with nothing but an idea to carry him really underlines Dunk’s vulnerability despite his stature.

It’s possible that it arrives later, but at the very least the My Dinner with Lyonel sequence is moved from elsewhere in the story, if not entirely new. The cynic in me presumes this was to draw a stronger link to a house that Game of Thrones viewers would be familiar with, and Scrotal Recall’s Daniel Ings certainly captures that Baratheon sleaze. But cynical as it may be, it also gives Dunk a window into how he won’t be able to hide in the way he had before. He walks into that tent trying to shrink himself, but he’s too tall to go unseen, and Lyonel struggles to interpret his intentions outside of the realm of kissing feet and kissing steel. The drunken reverie they achieve is not real, exactly, born of ale and the chaotic energy of the Laughing Storm. I don’t trust that Ser Lyonel would ever vouch for him the next day, or remember their stomp battle on the dance floor. But it’s a conversation Dunk needs in that moment, realistic about his chances but also reflective on the life he intends to lead.

And it’s a natural lead-in to returning to his camp to find Egg, cooking a fish over a fire, having followed him in a lamb cart. I’m guessing part of the logic of delaying Egg’s appearance is labor law-related (I always presume this with child actors), but it works to give us a clear picture of who Dunk is before he finds himself a squire. It also gives us a better understanding of the character’s earnestness: whereas he threatens to “clout” Egg when he’s playing bravado back at the Inn, by this point we know that he’s not going to reprimand or turn him away. He pushes back at Egg’s brazenness, but he above all sees himself in the young boy, and looks to Ser Arlan’s example in a way that—regardless of whether he was actually made a knight—is pretty knightly at day’s end. Their final moment looking up at the stars is reflective and sweet—the luck of the stars is theirs alone, them against the world.

The “them” is still in its nascent stages, but this episode uses our knowledge of that world to want to root for them simply because they represent a side of Westeros we haven’t seen since Ned Stark lost his head. Game of Thrones became the show it was because the world it was in was unpredictable and gruesome, but A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms reminds us of the more innocent side of that world, and brings it to life in ways that charm without feeling too silly or over-the-top. It’s a delicate balancing act, but one that I’m excited to see the show manage as it pushes forward.

Stray observations

- While this premiere is 40 minutes, the subsequent episodes are all closer to a half-hour from the looks of the screener site. It’s still technically being classified as a drama, I think, but it certainly adds to the contextual reasons we interpret this as a comedy compared to the novella.

- Composer Dan Romer, last heard on HBO for his work on the excellent Station Eleven, provides the lovely soundtrack here, a clear contrast from the work Ramin Djawadi did on Game of Thrones. It’s a great fit, and another bit of contextual distinction.

- I’ve never seen Peter Claffey in anything, but just the other day someone fancast him as Ryan Price in Heated Rivalry (he recently played in a charity hockey event), and it was hard not to see that when we got some conspicuous rear nudity in the stream, y’know?

- When we were discussing the winter schedule, someone mentioned the “reveal” in the novella that HBO was spoiling in its promotions, and I was initially like “Do I know this?” and then realized it was just what Egg stands for. Maybe it’s just me, but as someone who read ASOIAF and followed along with the show, that particular “reveal” was just common knowledge? But I’m interested to see how it plays out here.

- Perhaps not shockingly, the production value on the dragon puppet show was definitely a little higher than it was described in the novella, because television. But the sweet little moment with the narrator was the real purpose, as it was there.

- The visual shorthand of the series means that we recognize a Targaryen as soon as we see one, so there’s not really a “mystery” regarding the drunk man Dunk encounters at the Inn. But it feels safe to say that this is going to return to relevance, given what we know.

- I have to admit I didn’t entirely understand why the women were play-acting a death ritual? Was it just for the thematic purpose of the reminder that he only has one body, and to take care of it?

- One detail from the books that didn’t make it into the show: when Egg asks him if Dunk is short for Duncan, he doesn’t actually know the answer for sure, but just rolls with it. He’s been Dunk so long, and since he was so young, that he doesn’t actually have a grasp on his name or his origins. Curious if we come back to that (or the fact that he’s also from King’s Landing) as their relationship evolves.

- Much as this year marks the 15th anniversary of Game of Thrones’ debut, it makes fifteen years of writing and thinking about the franchise online for me, so thanks for joining me on the next phase of this journey. I don’t take the dialogue we’ve been able to have for granted, dating all the way back to this article from December 2010. Looking forward to the discussion among paid subscribers in the weeks ahead.

Comments ()